Thanks to my friend, Tom Johnston, for his eloquent review.

JUDGEMENT DAY

Paul Fenton’s Judgement Day is a creatively ambitious, risk-taking album that takes the concept of “guitar hero” in a different direction. Twelve eclectic songs, which include hypnotic “psychedelic blues,” straight-up rockers, Delta blues and other genres, tell a single story of an unnamed hero’s quest for the secret of happiness in a troubled world.

The Judgement Day tale follows the classic story arc of mythical quests, as described in Joseph Campbell’s textbook “The Hero With a Thousand Faces”: a problem is identified in the world; a hero is recruited to a quest for the solution; he finds adventure but suffers a crushing defeat, rises from the ashes and from an unlikely source attains the gift of knowledge that can help him and his world. But unlike “Star Wars” and other modern hero quest stories influenced by Campbell, Fenton doesn’t spoon-feed you his thoughts. He tells his entire story figuratively, in images, metaphors, hints, leaving much open to your own interpretation.

The lyrics are spare, but this album can tell you a lot with just a few words – things are hidden behind simple phrases, waiting to be found. Many of the songs contain plot twists – just when you think you know what the track is about, it dives you deeper into the topic or veers into something else, the gentle initial deception making the song’s actual point hit you all the harder

The opening track is “Lost in the Woods,” with the unnamed hero singing to a young woman – apparently his just-coming-into-adulthood daughter.

The beginning of the song seems to reflect such a parent’s usual worry – have I cautioned my child enough about the dangers of the big bad world? But later, it touches on a parent’s deeper fear – that the real danger to our children is not the dark woods outside but the ones inside – the darkness of pessimism, despair. For that problem, the hero has no easy answer.

“Lost in the Woods” raises the question of how such inner darkness might arise. Fenton answers in the second track, turning the title “Have You Heard the News?” into a mocking refrain as he deftly skewers the 24-hour news cycle’s incessant demand for our attention and its relentless focus on negative stories.

He drives home this point even further with “Learn to Fly,” which at first promises to be a bouncy, happy childish fantasy about flying, but a minute or two in turns on us with a punch in the gut. It’s not a child dreaming at all; the hero is experiencing an adult’s child-like wishes for magical solutions or supernatural powers when we see news accounts of tragedies too horrific for our hearts to process. The guitar chords that initially sounded joyful in fact are desperate. Traumatized but catalyzed, the hero is“recruited” to the quest. He vows to “learn to fly,” symbolically saying he will learn the secret of sailing happily above it all.

Over the next six tracks, the hero’s quest takes him to various possible sources of happiness. First up is “Winter,” a duet with the sweet-voiced Daisy Szabo, who reassures the hero that she will stay with him and that the “cold, cold winter” is not to be feared – “it won’t last forever.” Again,there’s a twist. Just as we begin to think the song is about finding perfect joy in a woman’s total commitment, she reveals her own anxiety about the winter ending. The bluesman is commenting on mens’ common fear about our women – that they will leave us in bad times — and womens’ corresponding mirror-image fear that their men will leave them when times turn good (in the spring). That tension can never be resolved, so relationships can be full of hope, but never certainty. No perfect answer here.

The Beatles are one of Fenton’s influences, so it’s not surprising that the hero next looks to George Harrison-style Hindu spirituality in Track 5, “The River.” A tambura joins the guitars as he lyrically references themes from Harrison’s signature album, All Things Must Pass. The song is mesmerizing, but the mysticism is confusing. Perhaps Eastern themes and instruments don’t translate. At last the hero calls out “Maybe I’ll meet you on that other shore.”

Which leads to “Red Tele Raga,” an instrumental in which Fenton flips the scenario, using his very Western red Fender Telecaster to play a very Eastern raga. He renders a sweet and soulful improvisation, but at the very end we hear some mysterious sharp metallic clanks, as though the guitarist musically gave up trying to unite the two cultures and let his slide clatter to the floor.

What about a return to Eden and idealized romantic love? After all, Paul McCartney once sang that there was nothing wrong with just wanting to “fill the world with silly love songs.” “Desert Island Girl” is an unnamed fantasy woman who the singer calls his “baby,” promising to give her “everything in the world.” We can practically feel the tropical breeze through the palm trees as the guitars conjure a private luau. It’s as over-the-top a silly love song as you can imagine, but as the last licks fade away, Fenton pulls an old Beatles trick– barely audible, ambiguous spoken words to end the track. Turn up the volume and you’ll hear a hesitant voice asking “How did that sound to you guys?” and a curt answer from what sounds like Fenton himself. Is he dismissing his own song by damning it with faint praise? Perhaps a return to Eden isn’t the answer, either.

“Skydog” brings more hope. The rock n’ roll number begins with a perfectly-conceived Rudy Richman drum solo, which somehow sounds positively tribal as it summons all to come gather ‘round and hear the hero tell the story of the late, great chieftain of the slide guitar clan, Duane “Skydog” Allman. Allman died tragically young, but the upbeat tempo and lyrics insist that we celebrate his rich musical legacy. Here and there we hear what sounds like Allman’s full-tilt guitar screech — licks that would be right at home in “Statesboro Blues,” “Whipping Post” and other Allman Brothers classics, but the hero isn’t copying or covering, he’s praising.

The hero seems to have found the secret to overcoming that inner dark woods — study and celebrate the lives and works of great artists who came before, and perhaps emulate them. It’s probably no coincidence that the following track, “Stella II,” is an instrumental acoustic guitar duet, like Allman’s masterpiece “Little Martha.” The quest appears fulfilled.

Then Track 10 brings the hurt. The deliberately distorted vocals and raspy, ripping guitar of the eighty-year-old Delta blues classic “Your Close Friends” remind the hero about real sadness not of our own making, or of the media’s — the pain of a friend’s betrayal.

Facing this reality leaves the hero at a loss in “Nothin’Left to Say.” Like a slide guitar Icarus whose hubris led him too close to the sun, he presumed too much by trying to “fly”to happiness. He ridicules himself for the attempt, questioning whether anything he has done has added any value –whether any of it was worth “fighting for.” No longer able to decide anything, he cries that he “doesn’t know the answers,” declaring his quest a failure. The guitar wails, falling, wings on fire.

The hero is down for the count, until redemption arrives from an unexpected source in “Judgement Day.” The hero sadly describes witnessing the slow death of a friend – and experiencing what Leonard Cohen called being “summoned… to deal with your invincible defeat.” The realization hits the hero: someday he will be the one lying there and facing judgment, perhaps from some higher power but certainly from himself.

Cohen said we deal with facing the inevitability of our death just by living life “as if it’s real, a thousand kisses deep.” Fenton doesn’t leave it quite so abstract. Lyrically referring back to “Your Old Friends,” the hero reflects that perhaps he could have been a better friend to the dying man. Other self-questioning follows and then he embarks on an extended instrumental trip, changing chord progressions, tempos, musical themes, even guitars, searching, searching. The artist’s point dawns on the listener — life is not about getting definitive answers but about continually asking whether you are living as the person you should be, forever seeking the truth about yourself. Perhaps it’s better to keep looking – not lost in the woods, just searching — and constantly asking – have I lived my life well today? Like Campbell’s universal hero, Fenton’s hero has obtained and brought back the knowledge that will help his world – that the “answer” lies in the questioning.

Music critic Dave Marsh, writing about Johnny Winter, said that blues men are artists who look for truth within themselves, going as deep within as they can stand. In other words, a bluesman digs inside – even when it’s painful – to find a piece of truth, then holds it out for the rest of us to look at. I think that this is what this album is about — Fenton trying to share what he’s learned about the world (and himself) along the way, even though the truth isn’t always beautiful or convenient and doesn’t provide the simple answers we might want to hear. This album isn’t’ just more songs about girls and cars, teen-age angst or somebody done somebody wrong stories. He’s laying out for our consideration his personal views on some fundamental questions, then letting the chips fall where they may.

In this era of albums deliberately homogenized so that all the tracks sound similar, Fenton has taken a risky course by recording in multiple genres and styles to tell his story. He takes another chance by asking his audience to forgo simple answers and to join him in thinking about these issues.

Certainly you don’t have to. You can enjoy the individual songs without getting involved in the story. But if you want to get the full benefit of the album, you’ll need to listen with two ears, an open heart and a thinking mind and decide for yourself whether you agree with the artist’s views on the benefits and limits of relationships, religion and romanticism. You’ll need to turn off the computer and the cell phone, tell your loved ones that you need about 70 minutes of private time, close the door, get comfortable, turn on the music, and search, search, search within yourself. Maybe you’l find that the messages this album lays down will ring true for you.

— Tom Johnston

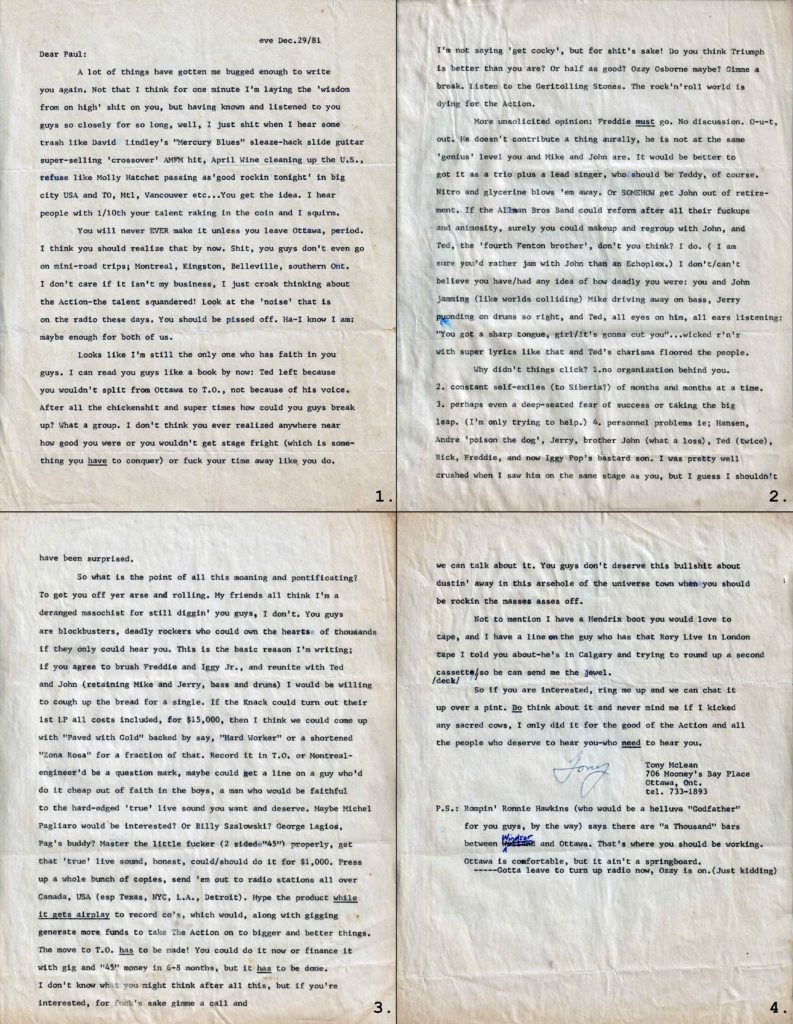

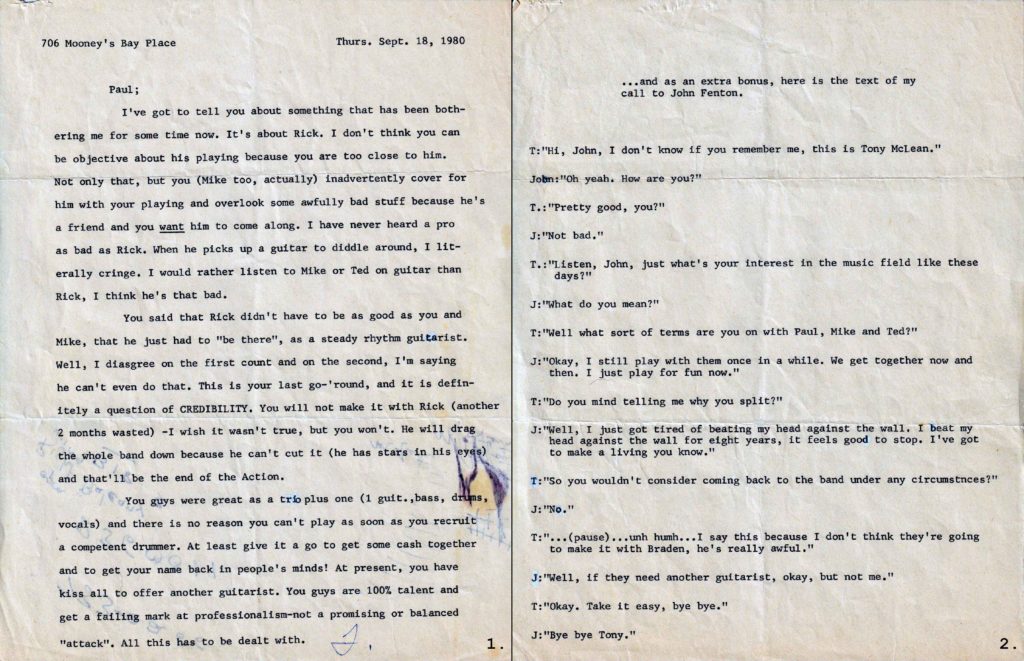

Letters written to Paul from his friend and former manager

Pep talk letters written to Paul from his friend and ex- manager…